The series “From the Archives” regularly features an article from the archives of our quarterly journal. The following article by Edith McCall appeared in the very first issue of the White River Valley Historical Society Quarterly.

While the United States of America was still an infant nation, it found itself in possession of a vast wilderness stretching from the Appalachian Mountain Range westward to the little scattering of French settlements along the Mississippi River. Immediately, hardy pioneering souls began to build their cabins and clear tiny farms in the woodlands.

But in all that land, from the mountains to the Mississippi, there was not a single wagon road adequate for carrying goods to the settlers. Even Daniel Boone’s famed “Wilderness Road” was only a packhorse trail. The rivers, especially the Ohio and its tributaries, provided the only highways.

Considering the small population and great problems of the new nation, it is surprising to learn how rapidly the Ohio River became a busy waterway to the western settlements. While Washington was still President, it was alive with rafts, flatboats, dugout canoes, barges and keelboats. The signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, marking the success of “Mad Anthony” Wayne in moving the Indians on to the west, gave further impetus to settlement, and soon there were three “western states-Kentucky, Tennessee and Ohio. The rivers carried their lifeblood-boatloads of needed goods brought in and surplus products shipped out. Without the broad rivers, the struggle for establishment of productive settlements would undoubtedly have been a far slower process, for land transportation was slow, laborious and expensive.

Then, while thousands of acres east of the Mississippi were still an untapped wilderness, the United States of America almost doubled its size. Through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the new nation acquired the mouth of the Mississippi River, so vital to the trade of the emerging “western” states. With it came the great pie-shaped wedge of land that formed the Mississippi- Missouri drainage basin. With access to ocean going ships at New Orleans’ harbor, the river trade of the American interior became more important than ever.

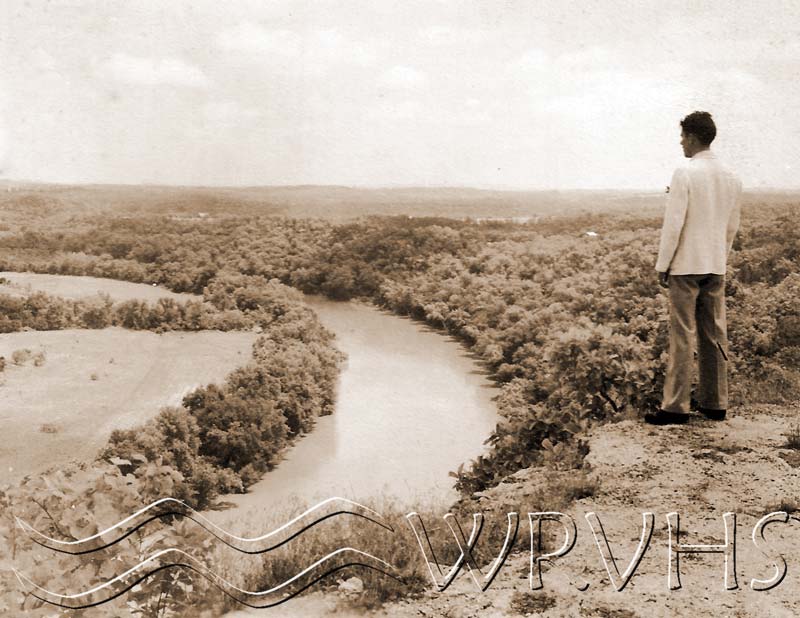

Among the commercial flatboats, barges and keelboats on the busy rivers were the crude, often homemade craft of the restless folks leaving the rapidly developing communities east of the Mississippi for unsettled lands in the west. The flow had begun even before the American flag flew in St. Louis, when Spanish governors, eager to see their vast holdings become productive, urged Americans to settle there and accept land grants. Some of the home-seekers in the early years, and more as American government became established, drifted on down the Mississippi to the mouth of the White River. Venturing up that winding stream, many chose its valley for their new homeland.

In his History of Taney County now in preparation, Mr. Elmo Ingenthron reports that by 1818, a thin chain of log cabins extended up the White River some three hundred miles to points near the future site of Forsyth, Missouri. By 1840 enough settlers had arrived in the upper White River watershed to have established not only that town and several others, but five counties with a population of nearly 20,000 people.

As the White River Valley became populated, the river’s role changed from that of an avenue of access for settlement of the region to that of a contact with the world the settlers had left behind. Self-sufficient as the early settlers were to a large extent, there were nevertheless always products of the outer world that they wanted. As their farms and woodlands furnished them with more goods than they consumed, they were ready to trade for toffee, tea, yard goods, hardware and cutlery and many another item. Access overland to the towns beyond the hills was very difficult. The White River was the best highway in the area.

Until the memorable year of 1811, the only forms of upriver transportation on all the rivers of the Mississippi- Ohio- Missouri system were powered by the muscles of sturdy men. No steam power had yet come to do battle with the inland river currents; it was the heyday of the semi-legendary Mike Fink and his rough and ready cohorts who called themselves “ring-tailed roarers” and ruled the rivers. They floated down stream with plenty of leisure for joking, singing and brawling. But to move loaded boats upstream against the river currents took every ounce of strength in their powerful bodies.

Their vehicles were the long, cigar-shaped keelboats, designed to give the least resistance to the currents. Occasionally these boats could move upstream with the aid of a square sail, an appropriate wind to fill it, and sturdy men at the bank of oars at the prow. Much more often, the keelboat could progress only through the poling, prodding and pulling of the men. With a long rope attached to the ship’s mast and run through a ring at the end of a short rope fastened to the prow, the men crawled over rocks and through bushes along the riverbanks, dragging the boat up the ‘river. Occasionally they could progress by “warping,”—tying the rope to a tree on the riverbank some distance upstream, and then turning a capstan on the deck to wind the rope and pull the boat up even with the tree. The crew were in the water and on the, banks more than they were in the boat; it took a rip-roaring “half-horse, half-alligator” to do the work.

Keelboats and their crews or small dugout canoes brought the first merchandise upstream to the little settlements on the upper White River. But with so much labor involved in moving a boatload of goods upstream, the inducement to journey to an upper river town had to be strong indeed. There was little trade so long as the keelboat era lasted. Goods could be taken down the river to market on a flatboat. But no one attempted to take a return load upstream by flatboat. Instead, that clumsy form of craft was always broken up at New Orleans or what ever its destination and sold for lumber.

In 1811, events transpired which were to ease the problem of carrying on trade in the interior. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, construction of the first steamboat to be used on the inland waterways was completed. Late in that year, the New Orleans chugged and puffed and clanked its way down the Ohio to Cincinnati and then on to Louisville. There it startled and amazed the westerners by demonstrating in short journeys that it could move upstream as well as down without the aid of sweating, panting men at the pulling end of a rope.

The New Orleans left Louisville late in the year, ready to continue its journey to New Orleans. Nature seemed inclined to fight the coming of the steamboat to the Mississippi, for it was just at the time that the New Orleans approached the confluence of the Ohio and the Mississippi that there began the terrible earthquakes of 1811, known as the New Madrid Earthquakes because they centered around that Missouri town. Daily the river’s bed shifted. Banks crumbled, trees crashed, and the river from time to time flowed backwards. Through a nightmare of storm and terror, the New Orleans moved on, miraculously escaping a thousand perils. Early in 1812, she was ready to carry goods upstream form New Orleans to Vicksburg, opening a new era in river transportation.

But it would be some time before the upper White River would see its first steamboat. After major re-designing of boilers, engines and deck arrangement, a successor to the New Orleans was made which was strong enough to master the Mississippi above Vicksburg. The New Orleans never was able to get back to Louisville, but in 1815 a boat piloted by Henry M. Shreve triumphed in that effort. Then, in 1817, St. Louis’ riverfront saw its first steamboat, the Zebulon M. Pike. Two years later, a steamboat with its hull shaped like a dragon, a prow that spewed out flame and smoke, and a rear paddle wheel that churned up the river, successfully journeyed up the Missouri River almost as far as where Kansas City is now. This boat was the Western Engineer, so fantastically designed in order to frighten Indians into submission.

With the major rivers mastered by the steamboat, pilots began to try the lesser rivers which were their tributaries. Soon steamboats were visiting the settlements on the lower White River, but the upper White River continued to be served by only an occasional keelboat until some of the obstructions in the river could be cleared away. There were masses of floating logs which collected at times of flood, and shoals which could not be crossed in times of lower water levels. Representatives of Arkansas and Missouri began to urge Congress to aid in the opening of the upper river to trade.

The Jefferson City Jeffersonian Republican of September 3, 1836, noted an appropriation bill as follows: “For the survey of the Saint Francis, Black and White Rivers, in Arkansas and Missouri, to determine upon the expediency of removing the natural rafts thereon, one thousand dollars.”

It was at this time that the young town of Springfield, Missouri; was beginning to ‘flex its muscles and to look for transportation routes to the Mississippi River, still the main artery of commerce for inland United States. Unlike most cities of its day, Springfield was not built on the banks of navigable river. Road building was one of its first and most urgent needs. The route to St. Louis, paralleling present-day Highway 66, was a rough trail with many river-crossings, and provided at best an expensive and slow avenue of commerce. Boonville Road, leading northward from Public Square, was used to take goods by wagon to the nearest point of navigation on the Osage River, at Warsaw, or, when the Osage was low, on to Boonville on the Missouri River.

The citizens of Springfield eyed the James River, flowing southward from near their city to a confluence with the White, and began to urge opening of the White River to upstream steamboat trade as a help to them.

Speaking of the White River, the Springfield Advertiser of July 9, 1844, said: “We are not a little surprised that this stream has heretofore attracted so little attention; from all we have been able to learn about it, it is decidedly a stream of more importance to the people of the southwest than the Osage; not that it is better or larger, but that it is equally as good at all times and seasons, and is a safe and convenient outlet for the surplus produce of the farmers, at a time when the Osage is not, in the dead of winter; and more or less flat boats have went out of it every winter for the last ten or twelve years, with perfect safety. The only difficulty of any magnitude in the way, is the Buffalo Shoals. In the fall of 1842, Maj. John P. Campbell of this place, being engaged in the boating business, with some four or five hands, in two weeks cleared out a passage through these shoals, eighty yards wide, for near a mile and a half.

“A gentleman of wealth and responsibility told us the other day that for forty thousand dollars he would bind himself in a bond of one hundred thousand dollars to remove every obstruction in White River, from the mouth of Bull or Swan, to Batesville, in Arkansas.

A steamboat captain in May of that same year wrote to Major Campbell as follows: “I have just returned from the Buffalo Shoals with the steamer Carrier, a boat of 350 tons burden. I started for the mouth of Swan, and could have reached that point with all ease… had it not been for the great rise in White River, it was impossible to make any head against such a tremendous rise and consequent strong and rapid current, without any other wood to make steam than water soaked rails and perfectly green wood that we were compelled to chop on our way.

“You may rest assured that White River for its length and size is one of the best in America for steamboat navigation, as far up as the mouth of the Swan, and with a small appropriation from Uncle Sam at the White House, it would be superior … The time is not far distant that will make the mouth of Swan a place of note in the map of southern Missouri. It must eventually be a place of deposit for all that tract of rich and fertile country lying around and west of it

In March of 1851, the Missouri legislature took action to improve the White River. Combined with its appropriation was some private capital, invested by prominent citizens of the Springfield area to aid in opening the trade route to them. We learn of a steamboat attempting to reach Forsyth that summer, but being forced to drop downstream some two miles below the Arkansas line. The work of deepening the channel at the shoals had begun by then. There are records of “Hack” Snapp being employed to cut a new channel through the shoals near the mouth of Elbow Creek in 1851.

“The next spring, the steamboat Yaw Haw Ganey approached the new channel,” writes Mr. Ingenthron. “All day long the steamboat labored in the channel trying to pass over the shoal. A number of passengers disembarked to lighten the load and waited on the banks of the stream. Still, the Yaw Haw Ganey failed to make the shoal and was compelled to back down stream and unload 300 sacks of salt belonging to the merchants of Forsyth. The following day, she ascended the shoal and completed her trip. Jim and Tom Clarkston were employed to haul the salt by ox wagons overland to Forsyth.”

Usually, the first method a steamboat captain tried in an effort to get his craft out of a shallow place was to alternately run his paddle wheels backward and forward so as to deepen the hole and free the boat. Most of the steamboats which attempted to navigate rivers with shoals, which included most of them other than the lower Mississippi and the Ohio, carried an additional aid in moving out of the shallows in the form of long poles and a pulley arrangement. These, poles were called spars. When the spars were in position for use, they looked like the legs of a great grasshopper, and gave rise to the term “grasshoppering” for their mode of freeing the boat. With the aid of capstan and tackle, the steamboat literally lifted itself as these long poles rested on the river bottom and the steamboat swung itself forward.

Another method, apparently much used on the White, was reminiscent of old keelboat days. The crewmen jumped into the water, dragging a towline with them, or rowed with it up stream in a small boat. They tied the rope to a tree as the old river-men had done before them. But the men on board the steamboat had the power of a small “donkey” steam engine on the deck to turn the capstan.

Farmers along the river had an extra source of money when the steamboats plied the river through keeping a woodpile at the river’s edge, ready for purchase by the steamboat captains. At a woodstop, the roustabouts, and sometimes also deck passengers who thus earned their passage, would hustle to the shore as quickly as the gangplank was set and haul the wood on board. A boat usually took twenty or more cords on board at a time, unless its cargo was unusually bulky. A half hour stop was usually enough to get the load on board and stacked near the furnaces. At a selling price of $2.50 a cord, a farmer who had woodland and was willing to work could add considerably to his cash income in this way.

By 1853, the White River had been worked over well enough for steamboats to come to Forsyth except in times of very low water. The Springfield Advertiser, in June of that year, re ported: “The Steamer Ben Lee has already made three trips, and is expected to be up the fourth time in a few days. She has brought loading for the various houses at Forsyth, Galena, and other points on the river, which will enable those merchants to sell groceries much lower than heretofore.”

Until the War Between the States slowed traffic, steamboat travel was heavy from that time on. Ingenthron says, “Their upstream cargo usually consisted of salt, gunpowder, bolts of cloth, kitchen wares, firearms, quinine, plow parts, tools and numerous other items. After the upstream cargo was unloaded, the holds were reloaded with cotton, grain, beeswax, furs, herbs, meats, and sometimes livestock for downriver shipment.

“A few shallow draft steamboats ascended the White River to the mouth of the lames. In 1858, the Thomas P. Ray, piloted by George Pearson and Jesse Mooney, unloaded their freight at the mouth of the lames and took on a cargo of cotton. As she passed Forsyth on her return trip downstream, she had her upper deck gayly decorated with flags in celebration of her feat.

“The upper White River, with all its might, resisted the encroachment of the steamboats and their captains. In the long struggle, the old river claimed its fair share of victories. Wrecked hulks of steamboats and flatboats lay half buried along the watercourse as silent testimony to the river’s successes. A few of the steamers lingered too long before retreating downstream. One such boat was the Mary M. Patterson, owned by Morlan Bateman. The early summer drouth and low water of 1860 kept her at bay, anchored at the Forsyth landing all summer and fall.”

The decade following the War Between the States, with its heavy activity in railroad building, marked the downward trend of steamboat transportation elsewhere. But the railroad was late in coming to the remote Ozarks, and measures to maintain navigability in the White River continued to be urged and acted upon. Even when the railroad was built to Branson in 1906, the river continued to be important commercially. It was felt that goods could be transferred from steamboat to railroad car and vice-a-versa if navigability between Forsyth and Branson were improved. A boat, the John P. Usher, was recorded as having made the journey downstream satisfactorily, but it encountered trouble on the return trip at Bull Creek shoal. The passengers returned to Branson by land. Further improvement of the channel was needed.

The Forsyth Taney County Republican, in its issue of February 20, 1908, reported: “The good ship Moark… arrived at the port of Forsyth from Branson Saturday evening… having made the trip down the river in an hour and a half. The boat was met by a goodly portion of the population of this place, who were loud in their welcome of it and the crew.”

It was arranged to make the round trip to Branson and return on Sunday, but as the Republican reported, “The fates seemed against the expedition from the start, however, and a stop of a half an hour had to be made… to fix the pump which supplied the water for cooling the engine. After this all went merrily, the boat breasting the swift current well, and taking the shoals in brave fashion until the mouth of Bull Creek was in sight. This is perhaps the worst pull on the river to Branson, and while pulling up, one of the paddles was lost from the right hand wheel, while the engine misbehaved somewhat. This necessitated the tying of the boat to the willows in mid stream while repairs were made which took about an hour.”

“In overhauling the engines one of the pipes was broken, and for a time, appearances were favorable for a night in the middle of the river. However, by dint of tying up the injured member with rags and string… a temporary repair was made, which held good until the return trip of about fourteen miles to Forsyth was accomplished.

The next month, on March 26, the Republican noted, “On its trip down the river the freight boat Moark went aground on the Franklin shoal. It was held there all night. It had on 5,000 pounds in freight.”

“The Moark,” says Ingenthron. “made a number of round trips from Forsyth to Branson and back when the water level in the river would permit. Records indicate it transported up to eight tons of freight on its return trips from the railroad. But even the Moark’s days were numbered, for in 1911 and 12, the Powersite Dam, an obstacle more formidable and insurmountable than the natural fury of the river, rose to close the curtain on the turbulent era of steam boat travel and trade on the upper White.”

The White River’s role had changed again. Replaced as a highway by the railroads and soon after by improved roads over which trucks carried the commerce of the Ozarks, the White is still the key to the region’s success. Impounded as it is over many miles of its length as dams much greater than Powersite created dragon-like lakes, the river answers modern day needs for power and recreation. In its new role, it brings more people than ever before to the wooded hills.

(Grateful acknowledgment is made to Elmo Ingenthron for the use of a chapter of his unpublished manuscript and to Donald H. Welsh former Assistant Editor of the Missouri Historical Review for research notes prepared for his address before the White River Valley Historical Society on June 25, 1961. E. M.)

This article by Edith McCall, originally appeared in the White River Valley Historical Society Quarterly Volume 1, Number 1—Fall 1961. Click here to browse or search the archives of the Quarterly.